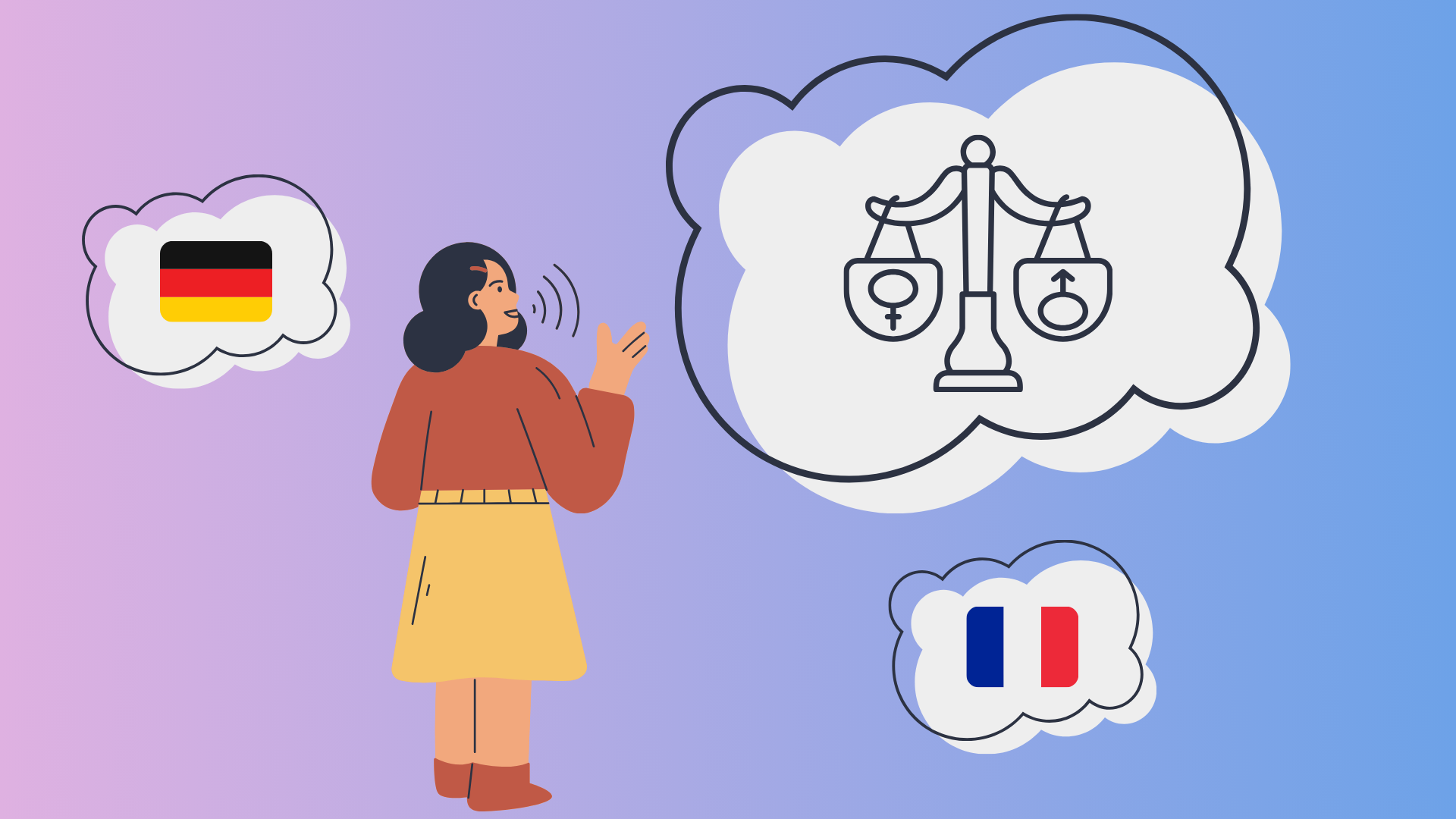

Inclusive language has been debated for several decades in France and Germany. Some see it as a feminist advance and an issue of visibility for women in society. But others find it unnecessary or even degrading for their language. A comparative view on the debate via political science, history and (variations) linguistics.

A feminist advance for some, a decline in language for others. Gender sensitive language is constantly debated, both in France and in Germany. But what differences regarding this topic exist between the two neighboring countries? And are there perhaps even similarities? The following article compares both countries in regards to usage and arguments of gender sensitive language, viewpoints of institutions and presents expert opinions, as well as an in-depth interview.

According to the German journal “Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte” from 2022 of the “Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung” (German institution whose goals are the promotion of democratic values and political participation) gender sensitive language tries to make women visible through language, because our world does not only consist of males. The generic masculine makes a lot of people invisible and is part of the French and German language: this rule makes a group of females and males appear as it only consists of males. Even though this rule has been used for a long time – although it has not always been an absolute rule – some believe that this is no reason not to question it. Especially because the generic masculine cannot be as neutral as it is always claimed. The fact that a lot of women and non-binary people fight for these changes, shows that there are still problems regarding sexism in society, including in France and Germany. Therefore, gender sensitive language is an important tool of equality, because language creates reality and reality creates language, so how we speak and write expresses our beliefs and can affect what we imagine.

However, different ways of including women in language coexist. Gilles Siouffi, professor of French Language at Sorbonne University – specialist in the history of the French language – illustrated this point by comparing French and English language: “We need to distinguish between two strategies: gender neutralisation and feminisation. The first is predominant in English, particularly with the use of « you » in the plural and the pronoun « they ». In French, feminisation is much more accepted, for example with the double feminine/masculine form, but the neuter pronoun « iel » is much contested.”

But the new use of gender sensitive language brings up a lot of criticism according to the journal of the “bpb”: people in both countries argue that it’s not grammatically correct. They also state that it’s difficult to read and understand and criticize that it’s forced upon them; they are not comfortable with it as it questions the binary gender system of man and woman. Some people, especially older people, find it hard to accept these new language changes because they feel it compromises their identity. Indeed, language is connected with identity as it shows who we are. Other opponents judge that there are more serious problems in both societies, for example the gender pay gap.

French Institutions Are More Conservative on the Subject

There are a lot of similarities regarding gender sensitive language in both countries, but there exists one big difference: In France, inclusive writing is still contested by institutions such as the government and the “Académie française”, defending conservative positions on inclusive writing. In 2017, this French linguistic institution, which aims to « contribute on a non-profit basis to the improvement and influence of letters« , described inclusive writing as a « mortal danger » for the French language, arguing that it would result in « a language that is disunited, disparate in its expression, creating confusion that borders on illegibility« . While this institution has no normative authority over the language, it does have a role of moral authority due to its history and the prestige of its members. Its opinions and recommendations, published in the “Journal officiel”, are a reliable source of linguistic information for many French people.

The circular introduced in 2021 by former Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer is a good illustration of this. It prohibits the use of inclusive writing in schools, more specifically in its most controversial form today: the use of the mid-point (e.g. “enseignant·e” in the singular form and “enseignant·e·s” in the plural form). Recently, on May 15th, the Grenoble administrative court illustrated this point: It called to order the University of Grenoble, which had drafted its statutes in inclusive writing. To justify this decision, the judges cited the need for the language to be accessible and understandable.

While inclusive writing seems to be meeting with a great deal of resistance, the feminisation of professional names and functions is becoming increasingly accepted in France. Forms such as « madame la mairesse/ ministre », « professeure » and « auteure » are becoming more commonplace. Even the “Académie française” has accepted this type of feminisation, in a note published on 28 February 2019. In it, the « immortals » – the name given to the members of the “Académie française” – state: « The feminisation of the names of professions, functions and titles raises a number of questions concerning the feminisation of the names of professions, functions and titles.” In addition to the feminisation of nouns, the use of the double form, with formulas such as « bonjour à toutes et à tous » (hello to everyone), is regularly used including political figures such as President Emmanuel Macron.

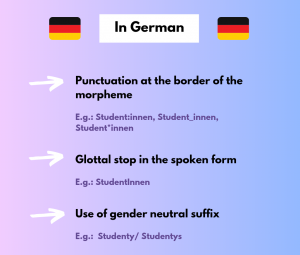

In Germany, the “Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache”, a German association supported by the federal government, the federal states and a funding group, which aims to promote awareness of the German language, has a different view of the gender sensitive language, which they released in an official statement on their website. In principle, the GfdS supports the demands for a gender-sensitive language and advocates the binary system in which both sexes are mentioned, for example, participle formation, pair formation or even a slash solution. Nevertheless, they wrote in their statement that they criticize that institutionalized change of language is “inhibiting natural language development”. The GfdS also rejects the view that the grammatical sex, i. e. genus, has nothing to do with the natural sex, the sexus, and also rejects all methods that “according to the rules in force today – grammatically and orthographically are not justifiable”. Nevertheless, “realistic and orthographically and grammatically correct options for a comprehensive gender-sensitive language still need to be discussed – this also includes gender gap (_) and gender asterisk (*)”.

A similiar opinion is voiced by the “Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung”, a board that is tasked with regulating the spelling of standard German since 2004. The meeting from the 14th of July 2023 concluded that the gender asterisk should not be officially recognized, meaning that it will not be a standardized German language character. At the same time, the board calls for tolerating the special characters in their press release: “The development of the subject is still going on and will be further observed by the board.”

A Practice that Divides Public Opinion in France and Germany

Beyond the institutions, inclusive forms are spreading into everyday language. German and French are living languages, and variations and changes are natural parts of languages.

Dr. Sebastian Franz – Variations Linguist at the University of Augsburg – explains that the question of how people change their language is a question of communication. “We interact with each other and when people communicate with each other, we adapt to our counterpart, which is a key reason for language change”, says Franz. According to him, this would happen because people naturally adapt to changing living conditions (e.g. globalisation, technological advancements, increased mobility) and want to develop the language further. Institutionally prescribed language change would also exist, but this would not be the organic way. Language change could happen very quickly. “You might get to know a new partner and develop a common code word, then this can become established very quickly, a new word and meaning can emerge, which you use again and again in a very specific context”, Franz says, but language change could also last for centuries. According to him, language and identity are fundamentally connected, because this is how group membership is shown. One would send direct or subliminal messages and “if I speak dialect, I can say I belong to a certain group, if I use gender sensitive language, I can express that I fight for equality, I can therefore show a conscious attitude towards these linguistic developments.” An argument often brought forward against gender sensitive language is the “decline” of the language, here Franz says that people put on “glasses”, through which linguistic reality is perceived. One of these “glasses” or ideologies is that language change would do harm. “The history of languages shows that change is part of every natural language. From a linguistic perspective, teenage slang and gender sensitive language are examples of language change, not language decline”, he says.

However, gender sensitive language is also still widely rejected by some people. In France, the main argument is the conservatist objection to language change. But the linguist Gilles Siouffi believes that it’s not a valid argument, at least for French language. ”In Old French, you could agree words according to the rule of the masculine gender or use proximity agreements. However, the generic masculine form still prevailed. It was at the beginning of the 17th century that grammarians systematised generic masculine agreement, but proximity agreements remained possible“, he explains. On the one hand, there exists the grammatical rule that says that adjectives become male as soon as at least one male is part of the relating group of nouns. On the other hand, the proximity agreement says that the gender of the adjective is dependant on the noun closest to it (e. g. “Les arbres (masc.) et les fleurs (fem.) sont belles (fem.).”, which translates to “Trees and flowers are beautiful.”).

In Germany, there are also people who do not accept inclusive forms of language, or at least don’t consider it important: 47 percent of women and 54 percent of men consider it to be very unnecessary, according to a survey conducted in Germany by the market research institute YouGov in March 2023.

According to the dossier on the website of the “Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg” (non-partisan educational institution that promotes political eduction, in particular in the German state of Baden-Wurttemberg), the voices in Germany also differ widely on a political level: some politicians are in favour of a ban on gender sensitive language, some even want its mandatory introduction. For example, the SPD, Die Linke and Die Grünen used the gender asterisk in the election program for the 2021 Bundestag election. Nevertheless, there is no statutory gender obligation at the state and federal level, but there is a mandatory establishment of linguistic equality in the municipal administrations of Berlin, Hanover and Munich in the official language usage.

A Subject at the Heart of Political Debate

Gender sensitive language has therefore become a widely debated political issue. Its use is even seen by some as a marker of commitment to the feminist cause. According to Eliane Viennot, Emeritus Professor of French Renaissance Literature at Jean-Monnet-Saint-Étienne University, language is political and conveys messages. For her, the rule of agreement in the masculine gender shows that the French language is still imbued with misogyny: « When we say that the masculine gender must dominate the feminine, it’s a way of saying that men must dominate women, that it’s inevitable« , she believes. She insists on children’s imagination, which she believes is influenced by the domination of men over women in the French language. « Schools teach that women are even less important than objects. In a sentence, when there is a woman and an object in the masculine form in the same sentence, everything is in the masculine form. Learning this rule confirms symbolic violence, and unconsciously legitimises other forms of violence« , she asserts. The academic goes further: for her, this issue is not just a question of agreements. She cites the example of the word « computer scientist », which is systematically used in the masculine form in French, whereas « cleaning lady » or « nurse » are often used in the feminine.

Gilles Siouffi has not the same opinion on the topic: he’s in favour of feminisation of words but for him, language is not political. “We need to distinguish between language and the use of language. Language in itself is not political; it is not enough to advance mentalities. I would say that languages are codes and that they can become political objects if we seize them to do something else with them”, he claims.

Viennot also highlights other possible solutions for dealing with agreement conflicts in language, in particular proximity agreements. This involves agreeing an adjective with the word closest to it in a sentence. This rule, which could go some way to solving the problem of gender in sentences, was more widely used in the past: « Our ancestors spoke, for example, of fundamental rights and freedoms, not fundamentals« , she illustrates.

About the French 2021 circular, the expert is critical: “We should drop these recent circulars that would like to ban inclusive writing when it should be promoting egalitarian language. We need to ask ourselves questions other than « Is there a man in the room?”.

Sources and further readings:

Amtliches Regelwerk der deutschen Rechtschreibung: Ergänzungspassus Sonderzeichen (2023)

Landeszentrale für politische Bildung BW, « Gendern: Ein Pro und Contra » (2023)

Thomas Kronschläger, Entgendern nach Phettberg (2022)

Anatol Stefanowitsch, Diagnose: « Männersprache » (2022)

Helga Kotthoff, Zwischen berechtigtem Anliegen und bedenklicher Symbolpolitik (2022)

Anne Wizorek, Vom Gender-Kampfplatz zum Sprachspielraum (2022)

Andreas Rödder and Silvana Rödder, Sprache und Macht (2022)

Interview with Jutta Hergenhan

“We Should Develop a Different Sense of Linguistic Norms, Think Less Error-Centered”

While inclusive language is a debate in both France and Germany, it is interesting to compare French and German language, and see how inclusive forms are perceived in the two neighboring countries. Dr. Jutta Hergenhan, political scientist with a focus on Gender and French studies at the University of Giessen, emphasizes on similarities and differences between French and German grammar in regards of gender sensitive language.

To what extent are there similarities and differences between German and French gender sensitive language?

Jutta Hergenhan: In both countries gender sensitive language is a political issue. There are people who think it is exaggerated to balance gender aspects in language or to make women visible on an equal footing and there are people in both countries who care about it, but also groups, media and institutions who are against implementing it.

In France, gender sensitive language became a political issue at the beginning of the 1980s, when the issue was the feminization of professional titles. In 1981, the French Minister for Women’s Rights, Yvette Roudy, wanted to encourage more women in male-dominated occupations, but found that very often there were no female job titles. This is a big difference to German, because we can attach the “-in” to titles, like “Schneiderin”. In Germany, the debate was sparked by the publication of “Gender Trouble” by Judith Butler in 1990, where she emphasized that masculinity and femininity are only constructs. Debates around gender sensitive language resulted to be no longer just about equating women and men within language, but also about gender plurality, contingency or neutrality. This debate is also taking place in France, but different morphological solutions for gender sensitive language have been proposed here.

In which country do people know more about how gender sensitive language works?

J. H.: In France, the first government directive on the use of gender-equal language was issued in 1986. It implied the use of “feminized” job titles or public mandates when women were referred to. These government instructions for public administration were not the last ones. In 1998, the same directive was adopted again, with a comprehensive guide on how to feminize each and every profession following in 2000. But this still only referred to the binary system of men and women. However, recent governments have even banned “l’écriture inclusive”, which means that the use of inclusive language beyond the “feminization” of texts is not allowed in the public sector, for example schools. Like Germany, it is mainly practiced in an activist context. Even at French universities, gender sensitive language is very controversial. Nevertheless, several guide books on the subject have been issued in France and, there is still an on-going public discussion. In Germany, the “Dudenverlag” published the guidebook “Richtig gendern” by Gabriele Diewald and Anja Steinhauer and many city administrations have guidelines on how to use gender sensitive language. Still, in both countries people do not know how to use gender sensitive language because they don’t know what lies behind it – socio-politically and historically. Moreover, many people in both France and Germany are afraid of making mistakes, as linguistic mistakes are often socially heavily sanctioned and provoke shame. But in fact, gender sensitive language is not difficult to use. As there are many possibilities to speak and write respectfully, it is more about self-reflection and creativity than about fixed norms and mistakes.

Are there differences or similarities in the arguments for and against gender sensitive language in these two countries?

J. H.: In France, there is this argument that French is particularly beautiful and you can’t write literature with gender sensitive language. Similar arguments are often held in Germany, stating the German language is already perfect and that there shouldn’t be changed anything. This discourse is held for example by the linguist Peter Eisenberg. I consider these kind of arguments rather as a pretense. Of course it is no one’s intention to make the rules of language even more complicated than they already are. In truth, gender sensitive language is about the social and political inequality between men and women and everyone else. Language is a symbolic system. When only one gender is named, the others are excluded. In actuality, the grammatical gender is not necessarily linked with the biological gender, but masculine and feminine are present in the language. That is the case in both countries. And we have to deal with it. There is also a difference between France and Germany in terms of language: In France, language has an important function for national identity, and there is an institution responsible for the French language, the Académie française. There is no such institution in Germany. In both countries, the language is also heavily burdened by colonialism. In France, this has strong geopolitical implications until today.

How could there be more acceptance of gender sensitive language and how could Germany and France work together?

J. H.: I don’t think it is necessary to work together, unless any cooperation institutions from both countries would want to advance the matter and develop common arguments that support the equality of all genders in language and society.

However, I personally do not think that it is mainly a question of creating one particular new language norm, but to raise sensitivity for inequalities transported by language rules and uses, and to be creative in overcoming these inequalities. Gender inequalities is just one of many social inequalities, and we have many different types of discriminatory vocabulary in our languages. I think it’s more about students questioning language when dealing with it: what am I saying, who am I including or excluding? I think we should develop a different sense of linguistic norms, think less error-centered. Instead of asking: Am I allowed to do that?, we should rather have thoughts while speaking and writing like: How can I write openly and without stereotypes?

Article and interview by Viola Köhl and Marie Scagni

____________________________________________________

This article is a product of the project „Futur2 – French German Journalism“ by students of BA Journalism, KU Eichstätt-Ingolstadt and M1 Journalism, CELSA Sorbonne University. It was funded by Deutsch-Französische Hochschule | Université franco-allemande: „Élysée-Vertrag – Zusammen den Blick in die Zukunft richten“ in 2023.